Most human biosamples originate in the public sector, primarily from public hospitals and publicly-funded biobanks. This reliance on public sources highlights the need for robust public-private partnerships to support human tissue procurement for private industry. While commercial biobanks and intermediaries play a significant role in supplying biosamples to industry, there is also a need to explore alternative routes for human tissue procurement.

Public-Private Partnerships in Biobanking

Various models of public-private partnerships exist to facilitate the interaction between biobanks and industry.

1. Direct Interaction

One common model is direct interaction between biobanks and industry. Many biobanks have agreements with industry to supply biosamples in exchange for a fee. Often, these transfers occur as part of research collaborations, such as translational research or clinical trials. However, these interactions, while seemingly straightforward, can be challenging to set up, because it is often difficult for industry to find suitable partners in academia.

2. Interaction Through Commercial Intermediaries

Another approach involves indirect interaction through commercial intermediaries. There are three main types of intermediaries involved in the commercial biobank sector:

- Human Tissue Procurement Companies or Commercial Biobanks: These companies specialize in supplying biosamples to the industry. They partner with hospitals and may operate internationally, often working with other human tissue procurement companies to meet the growing demand.

- Biobanking Brokers or Virtual Biobanks: These companies connect suppliers and requesters but do not operate a physical biobank. Instead, they arrange biosample transfers between the two parties.

- Contract Research Organizations (CROs): CROs provide a wide range of services to industry, including human tissue procurement.

Although these intermediaries play a crucial role, they are often overlooked in scientific literature. It’s essential to pay attention to their contributions to fully understand the complex ecosystem of human tissue procurement companies.

3. Interaction Through Non-Commercial Intermediaries

Another indirect approach is through not-for-profit intermediaries, such as the Expert Centre model. These not-for-profit companies serve as trusted intermediaries between biobanks and industry, ensuring ethical and reliable access to biosamples.

Similarly, the Biosample Hub, a global platform, connects non-commercial biobanks with biotech and pharmaceutical companies. It fosters global communication and collaboration, providing an alternative to traditional commercial biobanks.

The Lifandis Model is another example, where a publicly funded initiative in Norway bridges the gap between industry and the publicly funded HUNT study, providing a trusted interface for biosample access and research collaboration.

The Emergence of Human Tissue Procurement Companies

The role of commercial biobanks and human tissue procurement companies has grown since the 1990s, though they have received little attention in scientific literature. For example, Pharmagene, a UK-based drug discovery company founded in 1996, sourced biosamples from a nearby hospital for pharmaceutical research. In 2006, Pharmagene merged with a U.S. company to form Asterand Bioscience, a prominent commercial biobank.

Similarly, Genomics Collaborative Inc. (GCI), founded in 1998 in the USA, operated a dual business model, offering both fee-for-service biosample supply and collaborative research access to genomic data. In 2007, BioServe acquired GCI, expanding its tissue procurement service. Numerous other human tissue procurement companies, such as DNA Sciences Inc. and Ardais, also emerged during this period, contributing to the growing commercial biobank sector.

Growth of Biobanking Since the Turn of the Century

Since the early 2000s, the demand for biosamples has increased significantly, leading to a rise in commercial biobanks. A key driver of this growth was the U.S. FDA’s 2004 white paper, The Critical Path to New Medical Products, which emphasized the need for biomarkers in drug development. As a result, human tissue procurement became more critical, and the number of biobanks, especially commercial ones, increased.

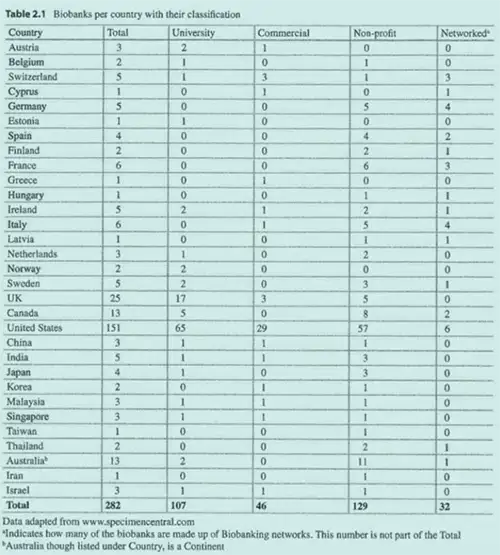

A 2015 study by Somiari and Somiari showed the global expansion of biobanks, categorizing them by type. The United States, with 29 commercial biobanks, led the way, followed by the UK and Switzerland with three each (see table 2.1 below). This data illustrates the growing role of human tissue procurement companies in the global biosample supply chain.

The Somiari and Somiari article is also notable because it is one of the few publications that mention commercial biobanks.

The Role and Significance of Commercial Biobanks

The impact of commercial biobanks goes beyond their number. Unlike academic biobanks, which often rely on institutional support and grant funding, commercial biobanks are driven by the need for successful transactions to make a profit. They provide most of their samples to pharmaceutical and biotech companies, and may operate with industrial efficiency to meet their demands.

Nevertheless, commercial biobanks do have some disadvantages. They may not offer sample traceability, because revealing sources carries a business risk of circumvention. Additionally, samples may be expensive due to the need for profit. Commercial biobanks also tend to focus on limited geographic areas, particularly Eastern Europe, reducing the diversity of samples. This profit-driven approach may also lead to missed opportunities for collaboration between industry and academia.

Conclusion

Non-commercial routes, including partnerships with public biobanks and not-for-profit intermediaries, offer essential alternatives to commercial biobanks in the realm of human tissue procurement. These routes provide benefits such as better traceability, lower costs, and greater opportunities for collaboration between academia and industry. By relying on publicly funded biobanks and population studies, these non-commercial pathways ensure broader geographic diversity in biosample sourcing, avoiding the limitations seen in the commercial biobank sector. Furthermore, public-private partnerships and expert centres act as trusted intermediaries, facilitating ethical access to biosamples while fostering innovation. As demand for biosamples continues to grow, these non-commercial alternatives will play an increasingly vital role in creating a transparent, cost-effective, and collaborative approach to human tissue procurement.

References

Woodcock J, Woosley R. The FDA critical path initiative and its influence on new drug development. Annu Rev Med. 2008;59:1-12. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.59.090506.155819. PMID: 18186700.

Other posts on this Biosample Hub blog include:

- Why Academic / Hospital Biobanks Should Provide Biosamples to Industry

- Ensuring Public Support For Biobank Cooperation With Industry

- The Main Actors Providing Biosamples To Industry

- Biosample Needs of Different Industry Players

- Acceptable Transactions in Biobanking

- What is Commodification?

- Why Biobank Access Policies Should Be Publicly Available

- Biospecimen Provenance: What Researchers Need To Know